(Published in Business Day – 25 June 2024)

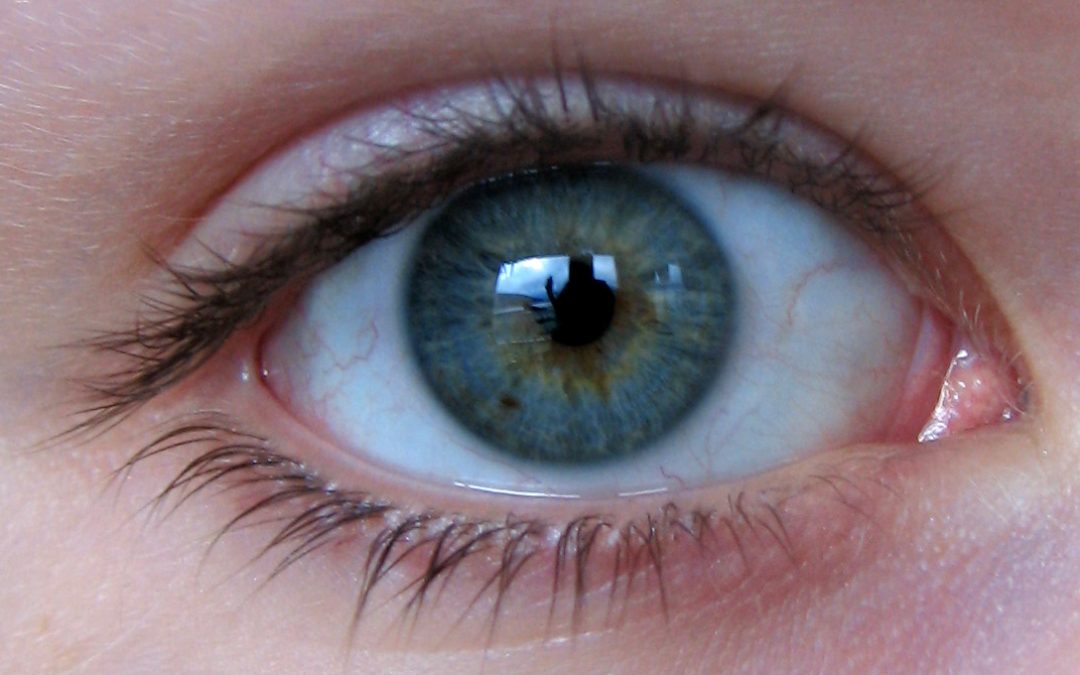

In 1968 Jane Elliot, a third-grade teacher in the little town of Riceville in relatively monocultural Iowa, USA, ran a daring experiment. She told her all-white class on the first day that those with blue eyes were smarter and better behaved than those with brown eyes.

All morning she selectively pointed out the mistakes brown-eyed children made and praised blue-eyed children. In just one morning she created a stark division in the class. Brown-eyed children had to wear collars to identify them and were denied privileges like playing on certain equipment at break or going back for second helpings of lunch. Why? “Brown-eyed people are greedy”. The impact was clearly demonstrated by the significantly poorer performance of the brown-eyed children on a card sorting task.

The next day she told the children that she had been mistaken. She reversed the order and selectively pointed out when the brown-eyed children were better and smarter. The performance difference between them on the card-sorting task was even more pronounced on the second day, with the brown-eyed children dramatically overtaking the blue-eyed children.

At a reunion 15 years later, the participants described how this experience had transformed how they saw others and themselves. It was a magnificent lesson in the harmful effects of prejudice and the helpful effect of a healthy self-image. It was also a very salutary lesson in how easily and extraordinarily quickly authorities can influence us to create a hierarchy of us and them.

She then replicated the experiment with adults. Again, in just one day, she created the same hierarchy with its effects on performance.

Watching the experiment and her very skilled debrief to restore the comradeship in the class shows effectively how systems of prejudice afflict us. Being told repeatedly that we are inferior becomes internalised and reduces our performance on objective tasks. This demonstrates very clearly the damaging impact of systems like apartheid and labels that denigrate people on the basis of gender, age, or any other demographic category.

I have used it often in management classes and seen how members begin to treat each other with greater respect as they realise the unfounded basis, and huge impact, of their often-unconscious behaviour towards those who are different. I enjoy even more the liberation expressed as people realise how they have been held back by the unfair limitations in their own minds created by the attitudes of others towards them – especially others in authority.

That brings us to the role of managers. We create organisational reality for our people. This can be either affirming or destructive. Jane Elliott created the division in her class by arbitrarily drawing attention to eye colour and attaching to it comments about performance that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. We too create reality by drawing attention to categories and attaching value distinctions to them.

For example, banks generally place higher status on the sexier units like corporate banking and lower status to the back office. One study showed that when people were transferred between different levels in the bank, on average their performance improved or dropped to match the status of the unit to which they moved. In what is known as the Pygmalion Effect or self-fulfilling prophecy, we tend to perform at a level that is expected of us.

This is a very powerful tool in the hands of those whose authority gives them power to influence the self-concept of more junior people. We often focus on the negative effect of this, but what really excites me is the positive effect. I have seen again and again how people blossom when affirmed.

Managing diversity is not just a political imperative; it offers an amazing opportunity to set captive people free to be extraordinary. This is one reason why I love the vocation of management.

Jonathan Cook chairs Thornhill Associates